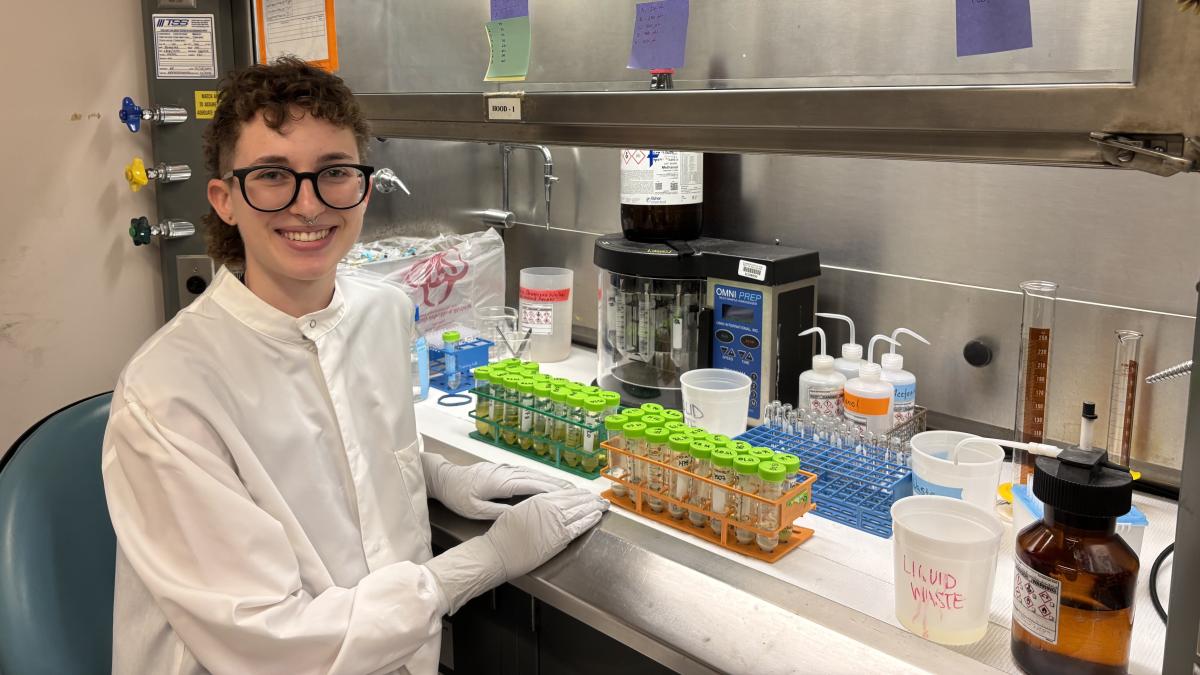

Katrina Gunvaldson

BS, Environmental Public Health

Hometown

Redmond, WA

Internship with

Washington State Department of Health Public Health Laboratories

Editor’s note: This summer, DEOHS students have been getting hands-on experience as interns with health agencies, nonprofits and private companies. In our occasional “On the Job” series, we feature some of their stories.

The coastal waters of Washington hold a bounty of shellfish for hungry harvesters armed with boots and buckets. But how do they know when it’s safe to feast? Katrina Gunvaldson’s work with the Washington State Department of Health this summer helps to answer that question.

The rising senior and environmental public health major is spending the summer at the state’s Public Health Laboratories in Shoreline, testing shellfish samples for biotoxins to make sure they’re safe for human consumption. If they aren’t, the beaches close to harvesters.

“During the summer, the toxins peak because they're produced by algae, and the warmer temperatures cause algal blooms,” Gunvaldson said. “So, summer's definitely the busy season for the lab.”

Beaches closed to harvest

This summer has already seen several beach closures, and Gunvaldson has been gratified to play a role in protecting public health.

“It's interesting to hear the stories of people who've gotten sick in the past. That’s not happening anymore because the program works so well and protects so many people,” they said.

“The labs here are protecting a lot of people very directly. That’s really cool to see, and it's definitely very inspiring.”

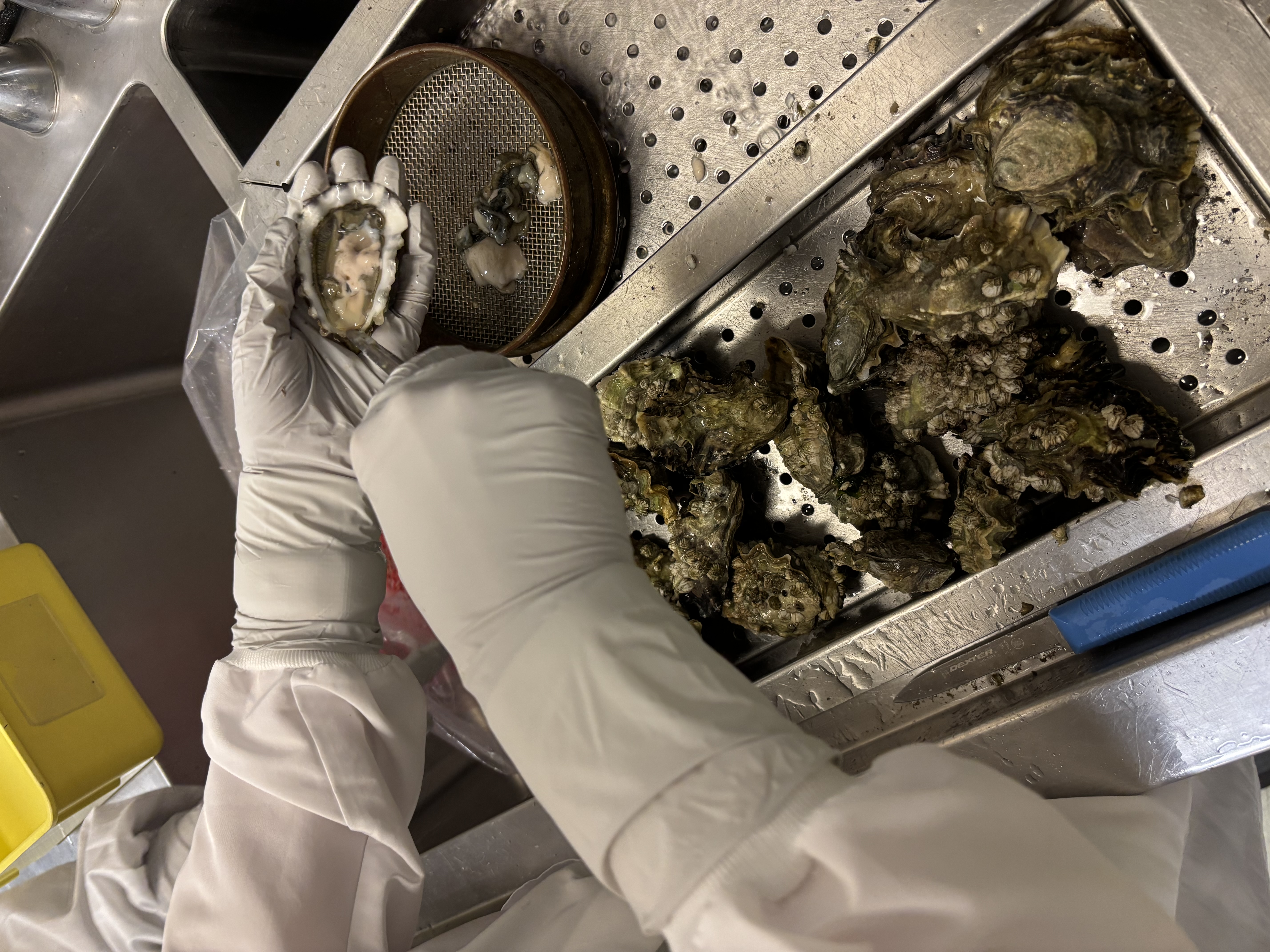

Samples of oysters, clams, mussels, geoducks and other shellfish arrive daily at the lab in Shoreline from various bays and coastal locations across the state. Gunvaldson handles intake and processing of the samples and marks each one for the appropriate test based on its origin.

Trio of toxins

The tests look for three harmful toxins: paralytic shellfish poison, amnesic shellfish poison and diarrhetic shellfish poison. These toxins, if ingested, can cause serious health effects, including paralysis, memory loss, diarrhea and even death.

Shellfish are filter feeders and accumulate poison in their tissues when they pump water through their systems as they eat. Cooking does not kill the biotoxins.

As a summer intern, Gunvaldson helps get the samples ready for each testing method, including shucking the shellfish and aliquoting – or weighing out – the right amount of tissue. In some cases, other prep is necessary. For example, the paralytic shellfish poison (PSP) test requires heating the shellfish tissue in acid to simulate stomach digestion.

While the final step of testing is handled by the lab’s professional staff, Gunvaldson said it’s been rewarding to see the science up close.

“I am a chemistry minor and environmental public health major, and this is an environmental sciences chemistry lab, so it’s perfect,” they said. “It's exactly what I'm interested in.”

Equipment validation

However, as the lab works to expand its capacity, Gunvaldson has been allowed to run additional testing on other instruments in order to validate the extra equipment, which has been an exciting opportunity for hands-on chemistry and data analysis. They’re currently working on an academic poster about the validation process.

Working for a government agency this summer has been rewarding in unexpected ways, Gunvaldson said.

“It’s a tight-knit community here in a very positive way, and everyone's here because they love their job. They love helping to protect the public,” they said. “I think that's really awesome, and people should definitely give it a try if they're interested.”